The Indian truth behind the ruins of Takshasila

The truth behind the ruins of Takshasila

Takshasila(Taxila) was a vital Buddhist centre from the fifth century B.C. to

the Sixth Century A.D. Takshasila illustrates the different stages in the

development of a city on the Indus. It included the ancient Neolithic Saraikala

mound, the Sirkap fortification (2nd century B.C.) and the town of Sirsukh (1st

century A.D.). Central Asian, Persian and Greek influence can be witnessed at Takshasila.

(Centre, 2023). Ancient Takshasila was situated at the pivotal junction of

South Asia and Central Asia. The common association of the Huns with Takshasila

has been the destroyer of the Buddhist structures at Takshasila. The name

“Huns” has been associated with atrocities committed against select groups and

vandalism, especially by Attila in Europe. However, no

reliable evidence exists of the Alkhan carrying out such atrocities and

destruction in the outgoing fourth century. New archaeological research has

revealed that this image does not correspond with historical reality.

Prof. Ahmad Hasan

Dhani, an eminent archaeologist, historian and linguist, writes in the

introduction of the book on Ancient Pakistan, “The archaeology of Pakistan in the post-Kushana period is ill

evidenced. On the suggestion of Sir John Marshall, it is generally believed

that the Huns destroyed the Buddhist monasteries in the 5th century A.D., and

they probably spelt disaster to the rich civilization built by the Kushanas

under the inspiration of Buddhism and on the thriving commerce with the East

and the West. Unfortunately, no heed is paid to the accounts of the Chinese

pilgrims travelled in West Pakistan either during the rule of the Huns or after

them. The analysis of their accounts tells entirely a different story. When these

details are combined with scattered pieces of archaeological material, we get a

completely new picture.”

The Kidarite Hun took over East of

the Indus in Punjab around Takshasila from the last Kushan kings ruling there.

The Indian kings pushed them into Kashmir after ruling here with the Alkhan

(Schörflinger, 2013). Historical sources and archaeological finds reveal that the

Alkhan Hun had expanded eastward across the Indus and reached at least

Takshasila. Four hunters are shown on a silver bowl found in Swat but

likely produced in Gandhara; based on their crowns and features, two can be

identified as Alkhan and two as Kidarites. After the Alkhans, the Karkota dynasty of

Kashmir ruled Takshasila, but there is no mention of destruction by Kalahana in his book Rajatarangani. The Chinese

Buddhist pilgrims continued visiting Gandhara sites in the Peshawar basin into

the early 6th A.D. Many visited the Buddha’s alms bowl shrine (Behrendt, 2004).

Kuwayama was the first to challenge the old assumption of percecution by the

Hun.

However, in their portrayal of the Huns,

the authors of Antiquity had nothing positive to say, describing them as

barbaric intruders. Xuan-Zang, also known as Hsiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk. He was also a

scholar, traveller, and translator. Hsuen Tsang visited Takshasila almost two

centuries after the Huns and blamed them for the destruction in his writings. As

per Xuan-zang’s description, in Gandhāra, there are 1000 sangharamas or Stupas,

which are deserted and in ruins. The stupas are filled with wild shrubs and are

solitary to the last degree. (Zang & Beal, 1884 This was not the case with

all the stupas. Xuanzang writes that the monastery at Pushkalavati was not

abandoned outside the city. Kanishka's stupa, the cruciform stupa at Shah-ji-ki-dheri,

was restored after being damaged (Zang & Beal, 1884). Xuanzang and Sun Yun

attribute the decline of the Gandhāran tradition to the Hephthalites, and

Marshall goes a step further to

suggest iconoclasm and the burning of monasteries

(Marshall 1951: 76-77). John Marshall was prejudiced as a European historian

and specialist in Greek Civilization history. The devastation carried out by

Atilla the Hun was probably why John Marshall

attributed the destruction of Takshasila to the Huns without differentiating

the various Hun tribes.

Scholars initially took these accounts as credible evidence,

assuming that sometime in the middle of the fifth century A.D.the Peshawar

Buddhist community of Gandhara was persecuted and that the sites were

methodically pillaged and destroyed (Behrendt, 2004). However, a

more recent and reasonable suggestion seems plausible that trade routes shifted

in favour of the Kabul Valley in Afghanistan, as there was an evident economic

decline in Gandhāra in the mid-sixth century. In all of these scenarios, it is

possible that earthquakes could have played a vital role in the rising and

falling fortunes of the Gandhāran tradition and may well have caused the

widespread destruction Xuanzang observed.

The Buddhist centres at Gandhara(greater)

were established very slowly, in different phases. Evolving masonry techniques

allow chronologically distinct construction phases to be distinguished.

1. Phase-I: Rubble masonry. Two independent

complexes were built. Butkara I and Dharmarajika, and a small group of sites in

the city of Sirkap.

2. Phase II: Diaper Masonry. More sites were

founded in this phase.

3. Phase III and later Phase III: Ashlar

Masonry & Double-Semi-Ashlar Masonry. Most construction occurred in the

Peshawar basin, Takshasila, and Swat. The architectural forms corresponding to stage

III account for perhaps 70% of the material that survives today. The most critical

phase III sites are Takht-i-barf, Sahrf-Bahlol, Jamal Garh1, Thareli, Ranigat,

Dharmarajika, Jauliafi, Mohra Moradu, Butkara I, Saidu, and Nimogram.

Construction appears to have occurred in Afghanistan, and

sites such as Bamiyan, Fondukistan, and Tapa Sardar thrived. In contrast, only

a few sites in the Peshawar basin and Takshasila had active patronage at this

time: Shah-ji-ki-deheri, Bhamala, Mamikyala, Bhallar tope, and probably the

Dharmarajika complex.

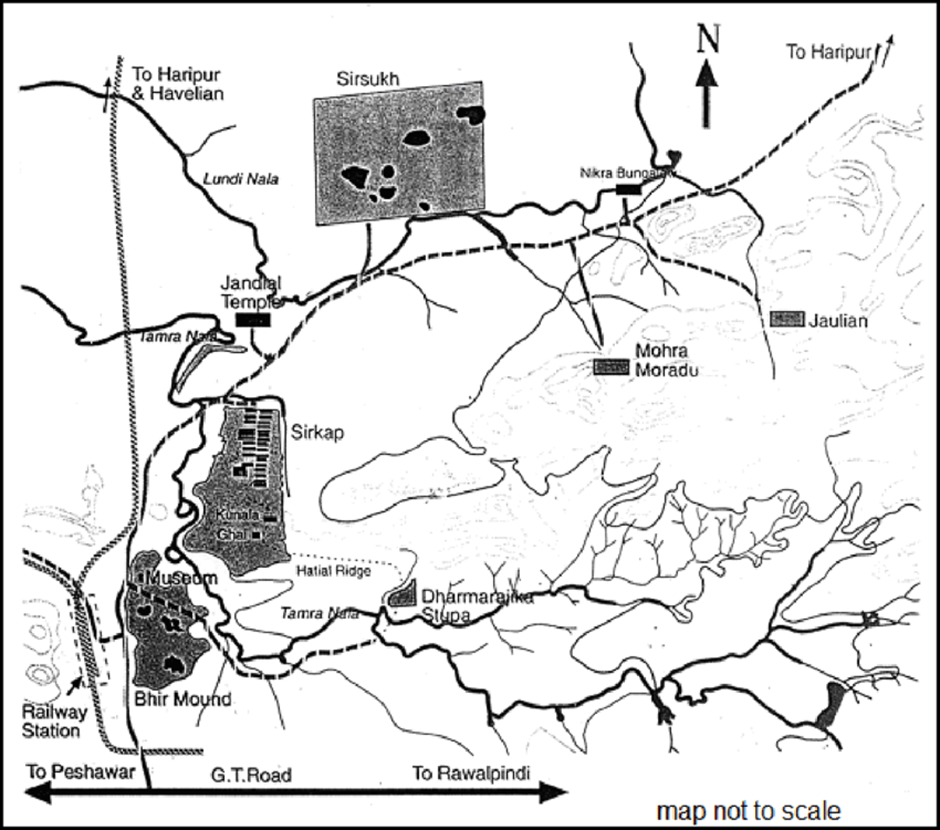

Figure : Map of Main Archaeological Sites

in Taxila World Heritage Site (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2010e).

A major proponent of the Hunnic destruction theories, Jhon

Marshall, Director General Archaeology, India, wrote in his book Taxila

(Takshasila) that “circumstantial

evidence leads no doubt that the White Huns were responsible for the wholesale

destruction of the Buddhist sangharamas(monastery) at Takshasila. Thirty-two

silver coins were found in the ruins of Takshasila. All but one coin was found

in the burnt-out monasteries, where some invaders perished. Several skeletons

were found at Dharamarajika monasteries, including one of a White Hun.”

The coins were probably minted North of the Hindu Kush, and names appearing on

the coins were those of "Jabula,” "Jarusha,” "Jatukha," or

"Jaruba." Marshall writes that these names were Brahmi variants of

"Javula" or "Jabuvlah." The coins were struck between

450-500 AD at a mint in Balkh(Marshall, 1951). Marshall's assumptions were

based on the fact that the last series of coins found at Takshasila belonged to

the Huns and no other later dynasty.

Kurt A. Behrendt is an associate curator of South Asian art

at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In his book, “The Buddhist Architecture of

Gandhara,” Behrendt quoted John Marshall and wrote that until now, these

theories had been accepted. The reason was that post-500 A.D., the patronage

for Buddhism appeared to have collapsed. This is why coins have not been found

at the Buddhist sites or in any archaeological records. This has been seen at

other sites too. This theory has been supported by the fact that sculptures

with sophisticated late iconography were not found at the sites. These are also

some of Xuanzang's "1,000 sangharamas, which are deserted and in

ruins" (Behrendt, 2004).

The Bamiyan Valley was a vital route

connecting the Silk Route with Southern countries like India. Xuanzang passed

through the area around 630 AD and described Bamiyan as a flourishing Buddhist

centre (Blänsdorf, 2009). Xuanzang was in Samarkand, North of the Oxus river

(Amu Darya). He would learn about Buddhism’s chief form of architecture, the

Stupa, and Buddhist Kings like Ashoka and Kanishka. Two monasteries existed,

but they had long stood empty before his arrival. He then travelled south to

the Oxus River, which rises in the Pamirs. Staying on the northern side of the

river, he remained in Termez. There he found Buddhism flourishing, with more

than a thousand brethren.

Finally, Xuanzang visited Balk on the advice

of the prince of Kunduz because of its many religious monuments. One hundred

monasteries and three thousand monks belonged to the Hinayana or lesser

vehicle. Above all, the countryside was rich in relics despite the invasions of

a series of foreign invaders. Buddhism flourished from the first to the third

century. During the third and fifth centuries, the cave monasteries at Bamiyan

and the thousands of Stupas at Hadda were constructed. The Buddhas of Bamiyan,

including the Western Buddha and the Eastern Buddha, were carbon-dated between

544-595 CE. Then came the invasion of the White Huns, who conquered Gandhara on

the way to India. Sally Hovey Wriggins was the first Westerner who

travelled extensively in Asia and retraced the footsteps of Xuanzang. Sally

writes that Xuanzang may have exaggerated their destruction; a combination of

floods, a general decline in economic prosperity, and, most importantly, a

general revival of Hinduism had occurred by the seventh century when Xuanzang

passed through the area (Wriggins, 2023).

Elizabeth Errington, in her paper “Numismatic evidence for

dating the Buddhist remains of Gandhara”, has supported the view that the Huns

did not destroy Takshasila, and there were several other reasons. She can no

longer sustain John Marshall’s simplistic view. She

writes that the Hun invasions must have impacted politically and economically.

For all periods, the monastic sites have produced very few stray coins finds, and

in some sites, none (Errington, 2015).

When making any numismatic assessment of this region, it is

necessary to remember that the lack of coin evidence in specific periods may be

because none were issued, and other forms of currency or the coins of earlier

dynasties were used instead. For example, the Palas of East India (c.

mid-eighth to the twelfth century) issued no coins but are known as a powerful

dynasty from other sources. As far as the Huns are concerned, coins of Kidara

are relatively numerous, but the Alchon coin-issuing group is known to date

only from hoards of silver coins found at Takshasila and Shah-ji-ki-Dheri, and

a single stray finds at Ranigat.

Hun coins of unspecified types have also apparently been

found during current excavations of the urban site of Hund. However, there is a

numismatic gap at all the other Peshawar Valley and Swat sites, including

Butkara I. This gap from approximately the mid-fifth century to the beginning

of the seventh ends at Butkara I with a coin of Sri Sahi (c. A.D.). The period

coincides initially with the conquest of these regions by the Alchon Hun rulers

Khingila (c. AD 440-90), Toramana (c. AD 490-515) and Mihirakula (c. AD

515-28), all of whom issued bronze coins (Alram, 2000). So-called Toramana

coins from Dharmarajika, listed by Marshall, Takshasila are, in fact, coins of Kashmir, issued in the

name of this ruler, or a later ruler of the same name, in the sixth-seventh

century.

The general absence

of their issues at sites north of the Kabul River and West of the Indus has

been relied upon to deduce the abandonment of the monasteries: after all, Song

Yun describes the Peshawar Valley in AD 519-20 as "the country which the

Ye-thas destroyed and afterwards set up Lae-lih to be king," a ruler who

was "strongly opposed" to Buddhism. However, the lack of bronze coins

datable to this period is not confined to the Buddhist sites but appears to be

a general trend throughout the region. If this is the case, the gap between the

Late Kushan/ Kushano-Sasanian bronze coinages and that of the Hindu Shahis

could be explained by the fact that none were issued in the interim, earlier

coinages may have continued in use or bartering or other currency forms were

adopted. Thus the lack of Hun bronze coins cannot be viewed as conclusive

evidence for abandoning the monasteries at this time.

Evidence in the form of coins lends credence to the theory

that the Kushan dynasty, which ruled the province of Gandhara

from the second century until the beginning of the fifth century, was

responsible for the growth and prosperity of the territory's monasteries. The

Hun invasion that occurred at that time has been blamed for the destruction of

the monasteries; however, coin discoveries and other evidence demonstrate, on

the contrary, that occupancy in some form lasted at numerous significant sites

into the eighth or perhaps the ninth century. As a result, it would appear that

the conclusion was not necessarily dramatic but rather was the result of a

multitude of events that affected various locations at various periods. It's

possible that natural calamities had as much of an effect on some situations as

the political and economic upheaval that was brought on by the Hun invasion. It

appears that the fall of the pro-Buddhist Kushan dynasty, the subsequent rise

to power of the Brahmanic Hindu Shahi, and, in Afghanistan at least,

eventually, the advent of Islam from the West were more significant factors

(Quintanilla et al., 2004).

As more archaeological evidence emerges, Marshall's

chronological framework for the end of Buddhism in the fifth century becomes

increasingly unsustainable. Ahmad Hasan Dani, for example, has already remarked

in connection with

the excavations at Damkot in Swat that "the evidence is not sufficient to

prove that there was a calamity [... or that this so-called] calamity was due

to the invasion of the \White Huns in the fifth or sixth century" (Rehman,

1969).

An important point to be considered in assessing the

factors that led to the end of Buddhism in Gandhara is the paucity of evidence

for the deliberate destruction of sites. For example, at Jamalgarhi,

Takht-iBahi, Jaulian, and possibly elsewhere, the stucco figural reliefs - indeed

a prime target for attack - were not vandalized but in pristine condition,

having been protected for centuries, until excavation, by fallen debris from the

collapse of the upper sections of the buildings. At Jamalgarhi, the complete

stucco figures of seated Buddhas encircling the main st[pa, excavated in 1852

and left in situ without protection, totally disintegrated within fifty years

after they were exposed (Bailey, 1833). This suggests that the collapse of the

buildings must have been quite sudden and was not the result of a gradual

process of decay over decades, else the stucco would not have survived.

Xuan-zang's record compares with the

archaeological and numismatic evidence elsewhere. He says that the people of Takshasila

were still Buddhists and mentions four monasteries that a few monks inhabited during

his visit

(Takakusu, 1905). The patterns of coin distribution at the Takshasila sites

support this assertion: notably, the finds at Bhamala, Lalchak, and

Dharmarajrka included Alchon Hun and other coins of the mid-fifth-seventh

century. However, the presence, at Dharmarajike, of images of the Hindu

divinities Vasudeva-Krsna (fifth-sixth century) and Skanda/ Karttikeya (sixth

century) indicates that the situation was not straightforward and that some

form of amalgamation of religion & cultures could have been evolving at

this and other sites in the vicinity.

Behrendt explains how an earthquake can explain the ruin,

as described by Sung-yun and Xuanzang. Unfortunately, no documentary evidence

supports the hypothesis, but the region lies in the seismic belt and has

witnessed periodic earthquakes. Calleri has observed a sixth-century earthquake

in Swat(Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), which accounts for the extent of destruction

(Behrendt, 2004). Marshall also suggested that an earthquake destroyed Sikarp,

and then it was rebuilt. Marshall writes about the temple at Jandial in

Takshasila, where several of the

columns and pilaster bases fractures were probably caused by earthquakes, and

the fractures were repaired by cutting back on the broken stones to straight

edges and dowelling on separate pieces using iron pins. If it can happen in

Sikarp, it could also be the reason for destroying other structures (Marshall,

1921).

Luoyang

Qielan ji describes Gandhara as follows:

“The land (of Boshafu, Varushapura, or

modern Shahbaz Garhi) on the rivers is fertile, and the fortified city is well

ordered, the population large and flourishing, the woods and the springs lush

and numerous. The land is rich with precious articles, and the customs are

refined and good. In and out of the city, there are old temples where virtuous

priests and monks reside, and their devout conducts are highly excellent. One

Chinese mile to the north of the town is a temple called the White Elephant

Palace (a palace of the father of Prince Visvantara), where all of the Buddhist

statues are of stone, extremely fine in decoration and very many in number. The

entire body of each statue is covered with thin leaves of gold, producing a

dazzling effect on the viewers. “

There is no

indication of abandoned temples or the decline of Buddhist activity here. This,

on the other hand, is true. This is an authentic pilgrim's writing that we are

aware of. It relates to the stone sculptures and images of Gandharan art covered in delicate gold leaf. (KUWAYAMA,

2002).

Abdur Rehman notes

that there is no reason to assume, as is generally believed, that Buddhism

disappeared altogether with the Ephthalite invasion of Gandhara in A.D. 455.

The Turk Sahis were decidedly Buddhists. The sites of Bambolai and

Damkot have now yielded Buddhist sculptures datable to the post-Ephthalite period. The evidence of some of the Tibetan

pilgrims to Swat has suggested to G. Tucci that Buddhism existed in this area

as late as the thirteenth century A.D. (Rehman, 1988).

The Hunnic rulers were more often donors of religious

monuments and presented themselves as an integrative power, equally open to all

religious and ethnic groups. Primary evidence about the History of East Iran recently

surfaced with a private collector in Norway. An inscription on a copper scroll

dedicating a Buddhist stupa in Tālagānika listed the names of several Alkhan donors

at the end of the 5th century. The names of Khīngīla, Toramāna, Javūkha, and

Mehama all were Alkhan rulers of the Turk Shahi dynasty. (Rezakhan, 2019)

Comments

Post a Comment